Lab 03 – Wrangling sales data

Instructions

Obtain the GitHub repository you will use to complete the lab, which contains a starter file named [lab03.Rmd]{.monospace}. This lab introduces you to data transformations using the [dplyr]{.monospace} library, which is loaded as part of [tidyverse]{.monospace}. Carefully read the lab instructions and complete the exercises using the provided spaces within your starter file [lab03.Rmd]{.monospace}. Then, when you’re ready to submit, follow the directions in the How to submit section below.

What is data wrangling?

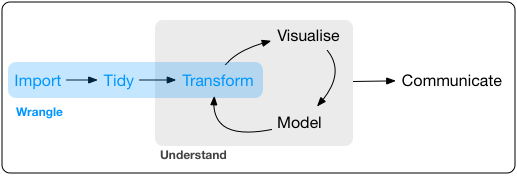

Lab 2 focused on constructing visualizations using the [ggplot2]{.monospace} library. The dataset used for that lab, the [galton]{.monospace} dataset, was selected because it was relatively small in size and could be visualized in interesting ways without the need for additional processing. It would certainly be nice if all datasets came in such a form! However, in reality, many datasets need to be cleaned, reshaped, and transformed before you can use them to create meaningful visualizations and answer interesting questions. Even datasets that have been preprocessed to be clean and tidy may still require you to apply transformations to help uncover the underlying trends in the data. The full pipeline for obtaining data, cleaning it up, and transforming it is informally referred to as data wrangling, which is summarized in the following figure from R for Data Science:

This lab introduces you to functions from the [dplyr]{.monospace} package that you can use to carry out the transform part of the data wrangling pipeline. If you have any prior experience with spreadsheeting software such as Microsoft Excel, you will probably find the functions in the [dplyr]{.monospace} package to be familiar.

About the dataset

This is a synthetic dataset that contains sales data for office supplies sold to clients in different regions of the United States.

The table below provides descriptions of the dataset’s 6 variables,

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| [order_date] | The date the office supplies order was placed |

| [region] | Shipping region in United States |

| [representative] | Name of sales representative |

| [item] | Item ordered |

| [units] | How many units of item were sold |

| [unit_price] | Price per unit of item |

Subsetting over variables

The [dplyr]{.monospace} package has many different functions in it and trying to understand them all at once can be a bit overwhelming.

So instead of listing everything all at once, we will build up our intuition by practicing with one function at a time.

Let’s start with the select() function, which allows you to select columns from a dataset.

This is useful when you’re working with a dataset that contains dozens of variables and you want to make things more manageable.

@select-column. Try running the following code:

```r

office_supplies %>%

select(representative)

```

Based on the output, explain what happens when you run this command.

Try putting an additional column name inside the parentheses of the `select()` command (don't forget the comma!).

What does this do?

:::{.callout .primary}

[Note]{.h4}

The strange looking symbol [%>%]{.monospace} is called the **pipe**, and it is a handy way to pass a dataset through a chain of commands.

All examples going forward will use the pipe whenever possible.

:::

There are multiple ways to specify columns with the select() command.

Let’s explore a couple of those ways.

@. Copy the code you wrote in Exercise @select-column and replace [representative]{.monospace} with [representative:unit_price]{.monospace}. What does the colon [:]{.monospace} do?

Next, try putting a minus sign in front of the column names, such as [-representative]{.monospace} or [-representative:-unit_price]{.monospace}.

How does the minus sign affect the output?

Sorting data

The sort operation is a common and indispensible operation for organizing data, and the function from [dplyr]{.monospace} that allows us to sort is called arrange().

arrange() sorts columns with textual data ([chr]{.monospace} data type) into alphabetical order and sorts numerical data into numerical order.

@. Run the following code:

```r

office_supplies %>%

arrange(region, item)

```

Based on the output, does it look like both the [region]{.monospace} and [item]{.monospace} columns were sorted?

Which column was sorted first?

What happens if you reverse the order of the columns in your code snippet?

By default, arrange() will sort data in ascending order.

The function desc() can be used to sort in descending order, and we can mix-and-match which columns are ascending and which columns as descending.

@.

Sort using the variable [order_date]{.monospace}.

Then, make a copy of the code block you just wrote and then wrap the column name with desc(), like so: desc(order_date).

Verify that desc() sorted the data in the reverse order.

Copy the starting code from the previous example, and adapt it so that [region]{.monospace} is sorted in *ascending* order and [item]{.monospace} is sorted in *descending* order.

Write it down and get the output.

::: {.callout .secondary} [Important!]{.h4}

Students often find that there is a base R function named sort() as well, leading to confusion later in the course.

Using sort() the same way you use arrange() will give you errors.

For the duration of course we will always prefer to use the [tidyverse]{.monospace} version of a function, so always use arrange() and pretend sort() doesn’t exist. :::

Transforming data

Let’s now try an example that uses the mutate() function, which is a little more complex.

mutate() lets us transform our dataset by applying the same operation to each row in the dataset and storing the results in a new column.

This would allow us, for example, to create a new column in the dataset called [total_price]{.monospace} that contains the toal price of each order.

@.

To calculate the total price of an order, we need to multiply the number of units sold by the unit price across each row.

Do this by running the following mutate() command:

```r

office_supplies %>%

mutate(total_price = units * unit_price)

```

After confirming that the above command works, copy this code into a new code block and remove [total_price =]{.monospace} from the function input.

Does the code still run?

If so, what (if anything) is different in the output?

What if you used `mutate(final_price = units * unit_price)` instead?

Based on these outputs, describe what the [total_price =]{.monospace} part of the command seems to be doing.

We are not limited to only one input at a time in mutate().

As long as we separate each input by a comma, we can put as many inputs as we want in the mutate() function!

@. Starting again with this example,

```r

office_supplies %>%

mutate(total_price = units * unit_price)

```

modify it so that there's a second input in `mutate()`, [shipping\_date = order\_date + 2]{.monospace}.

Does this add another column?

What has happened by adding the number 2 to the rows in the [order\_date]{.monospace} column?

Immutable datasets

It’s worth pausing for a moment and asking whether any of these commands are permanently changing the way the dataset looks in [office_supplies]{.monospace}.

Inspect your dataset by typing View(office_supplies) in the Console pane to check.

@. Based on what you observe, has each function we’ve run in the previous exercises changed the information in [office_supplies]{.monospace}?

As a comparison, run the command,

```r

office_supplies_updated <- mutate(office_supplies, total_price = units * unit_price)

```

Then, create a new code block with just [office\_supplies\_updated]{.monospace} in it, which will print it out for inspection.

Has the change stuck now?

Filtering data

Next up is the filter() function, which provides a ruled-based way to keep a subset of rows and remove the rest.

Here we just consider rules that are simple comparisons, which involve the symbols:

- [>]{.monospace}: greater than

- [>=]{.monospace}: greater than or equal to

- [<]{.monospace}: less than

- [<=]{.monospace}: less than or equal to

- [!=]{.monospace}: not equal

- [==]{.monospace}: equal

So, for example, a comparison rule that would show us all items that cost more than 16 dollars per unit would be [unit_price > 16]{.monospace}. A comparison rule that would find all rows with the representative Susan would be [representative == “Susan”]{.monospace} (if you are testing for equality with a column of [chr]{.monospace} type, then you need to surround any words or values in the column with quotation marks [“like so”]{.monospace}.)

@.

Give the filter() function a try by running the following two code blocks:

```r

office_supplies %>%

filter(unit_price > 16)

```

```r

office_supplies %>%

filter(representative == "Susan")

```

After running the above code, figure out how to write a single line of `filter()` code that shows us all the items sold by Susan that cost more than 16 dollars.

You should be able to do this based on what we've seen so far with the other [tidyverse]{.monospace} commands

Using filter() is a lot like running an advanced search on a data base, and gives us a convenient way to quickly look up and inspect subsets of data.

@. Write a filter that shows us all the sales that involved the [item]{.monospace} “Pen Set”.

Data aggregation

It is common to want to summarize the information contained within a dataset, such as computing sums and averages, or counting how many data points belong to different groups.

This is called data aggregation, as it aggregates many data points together and uses them to compute a cetain quantity.

We perform data aggregation in R by using the commands group_by() and summarize(), which frequently show up as a pair.

The group_by() command is applied to one or more columns, and allows you create groups that share common values in a column of categorical data.

The summarize() command can be used when you want to do things like calculate the average number of units sold by each representative, or calculate the gross earnings of each [item]{.monospace}.

@aggregation-practice.

group_by() and summarize() are functions that are easier to understand using examples.

First, run this example where we use mean() to calculate the average of a column:

```r

office_supplies %>%

group_by(representative) %>%

summarize(avg_units_sold = mean(units))

```

Which representative sold the most units on average?

Let's run another example where we add together the numbers in a column using `sum()`:

```r

office_supplies %>%

mutate(total_price = units * unit_price) %>%

group_by(item) %>%

summarize(gross_earnings = sum(total_price))

```

Which item brought in the most gross earnings?

Small changes to how we group our data can have a big impact on what our summary tables look like. This gives us a lot of flexibility in aggregating our data for analysis.

@. Take the second code example from Exercise @aggregation-practice and modify it so that it groups over two variables instead of one:

```r

office_supplies %>%

mutate(total_price = units * unit_price) %>%

group_by(item, region) %>%

summarize(gross_earnings = sum(total_price))

```

How did this change the summary table from what you obtained in **Exercise @aggregation-practice**?

Interpret the table you get as output.

Additional exercises

@.

The company wishes to expand their sales to include a new region, Canada.

Doing this would require converting the unit prices from US dollars to Canadian Dollars.

The current conversion rate is 1 US Dollar = 1.29 Canadian Dollars.

So, for example, an item that costs 2.99 US Dollars would convert to \(2.99 \times 1.29 = 3.86\) Canadian Dollars.

Using the mutate() function, write a code snippet that converts the unit price in US Dollars into Canadian Dollars and stores the result in a new column named [unit_price_canadian]{.monospace}.

@. Take the 2nd code example you ran in Exercise @aggregation-practice and assign it to a variable, like so:

```r

items_gross_earnings <- office_supplies %>%

mutate(total_price = units * unit_price) %>%

group_by(item) %>%

summarize(gross_earnings = sum(total_price))

```

Use [items\_gross\_earnings]{.monospace} to create a bar chart visualization of the gross earnings per item.

::: {.callout .secondary}

[Hint]{.h4}

You will want to use `geom_col()` for this.

:::

How to submit

To submit your lab, follow the two steps below. Your lab will be graded for credit after you’ve completed both steps!

-

Save, commit, and push your completed R Markdown file so that everything is synchronized to GitHub. If you do this right, then you will be able to view your completed file on the GitHub website.

-

Knit your R Markdown document to the PDF format, export (download) the PDF file from RStudio Server, and then upload it to Lab 3 posting on Blackboard.

Cheatsheets

You are encouraged to review and keep the following cheatsheets handy while working on this lab:

Credits

This lab is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Exercises and instructions written by James Glasbrenner for CDS-102.